One night last week, I was scrolling through my Twitter feed, when I can across a tweet claiming that the cure for depression is "a weekend of nature, sit[ting] under a tree and watch[ing] the water cascade over a cliff." As someone who has struggled with diagnosed clinical depression for a very long time, I was offended by this tweet. My response to it was: "Depression is a disease and chemical imbalance in one's brain, not an emotion. Stop #mentalhealthstigma & belittling the problem!" (Let's take a minute and think about how hard it is to tell someone facts and why they're wrong in 140 characters...) The replies I received were less than informed, and in some cases down right mean. I think my favorites were the ones that told me I was "brainwashed" and "Perhaps the chemical imbalance in your brain is a RESULT of you negative thinking/attitude" and "#YourHashtagsMeanAsMuchAsYourDegree #Nothing."

Depression is a serious mental illness that affects 5-8 percent adults in the United States each year. Less than half of these people will get help for their disease. This is a problem. Stigma and misinformed people are a problem. So let's look at some myths (and some arguments) that I came across in my Twitter fight.

Myth #1: Depression is not a disease.

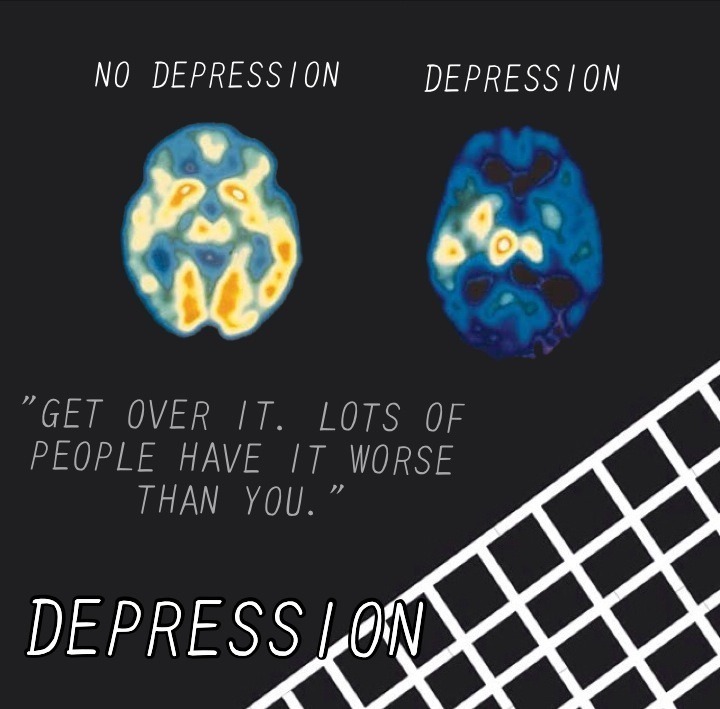

The dictionary defines disease as "a disorder of structure or function in a human, animal, or plant, esp. one that produces specific signs or symptoms or that affects a specific location and is not simply a direct result of physical injury." By this definition, depression must be a disease because brain scans have shown decreased activity in certain areas of the brain in depression patients, higher levels of stress hormones, and various genetic and biological causes that cause symptoms impacting one's thoughts, feelings, behavior, mood, and physical health. For some, depression is a life-long condition in which periods of wellness alternate with recurrences of illness. Depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide and represents a global public health challenge. According to the World Health Organization, it is the forth-leading contributor to Global Burden of Disease, and by 2020, depression is projected to be the second-leading cause.

There is no doubt, then, that depression is an illness.

Myth #2: Depression is a disease.

This is intentionally contradicting the point I just made. Depression is a disease, but it is not a straightforward medical disease. Confused? So was I, don't worry. Dr. John Grohol explains it in this way:

Diseases are manifestations of a problem with some physical organ or component within the body. And while the brain is also an organ, it is one of the least understood and easily the most complex organ within the body. Researchers and doctors refer to a diseased organ when something is clearly wrong with it (via a CAT scan or X-ray or laboratory test). But with our brains, we have no test to say, “Hey, there’s something clearly wrong here!”

One could make the argument, as many have, that because brain scans show abnormalities in certain biochemical levels within the brain when they suffer from depression or the like, this “proves” that depression is a disease. Unfortunately, research hasn’t gotten quite that far yet. The brain scans show us something, that much is true. But whether the scans show the cause or the result of depression has yet to be determined. And more tellingly, there is a body of research that shows similar changes in brain neurochemistry when people are doing all sorts of activities (such as reading, playing a video game, etc).Depression is not a pure medical disease in the traditional sense, but a mental illness or mental disorder. It is complex in that reflects its basis in psychological, social, and biological roots. While it has neurobiological components, it is no more of a pure medical disease than ADHD or any other mental disorder. Treatment of depression that focuses solely on its medical or physical components — e.g., through medications alone — often results in failure.

Dr. Azadeh Aalai relates it in this way:

Psychiatrists oftentimes use the parallel of the diabetic who takes insulin to treat his condition; so, too, must the depressive take his or her meds, they claim. This is a wildly inaccurate parallel for a number of reasons. Firstly, one can definitively diagnose and validate diabetes as a medical condition. One can also identify with certainty the underlying medical reasons behind the diabetic’s condition. Lastly, one can also identify with certainty the extent to which the disease can be controlled/treated with the administration of insulin (in the case of type I diabetes in particular). There is no definitive blood test or otherwise physical examination that can determine a depression diagnosis. In fact, contrary to the entire medical paradigm, the symptoms of the illness actually serve as the basis of the diagnosis in the case of depression. Moreover, there is not a clear intervention, medical or otherwise, that can be implemented for a depressed individual that will work in all cases.Summary: Depression is a mental disorder or mental illness--not a disease purely in medical sense, but it is still a disorder.

Myth #3: Depression is a product of your environment.

This one made me laugh a little bit. The boy who said this was clearly confused because he gave an example of a kid being depressed because his parents were fighting. First of all, that is not clinical depression--that's sadness. The two are not synonymous, but I will get to that later. Second of all, all mental illnesses are biopsychosocial in nature.

The first component is biology, which includes both the biochemical makeup of the brain, as well as inherited genes. Neurochemistry, especially neurotransmitters like serotonin, has been shown to correlate with depression, but the brain is so complex, that much is left undetermined for certain. Lately, research has started to show a genetic predisposition to mental illnesses like depression, but none of this determines if an individual will be affected. Having a relative with depression only increases your risk for getting depression by 10-15 percent. Correlation does not equal causation. The second component of this model is psychological, which includes a person's personality, how he or she was raised to deal with stress, how he or she deals with emotions, and other aspects. The final component of this model is social, which includes relationships and how we interact and communicate with others.

The biopsychosocial model is the most widely accepted model in all of psychology because it states that mental illness cannot be caused by biological or psychological or social factors alone--it takes a combination of all three to bring about any mental illness.

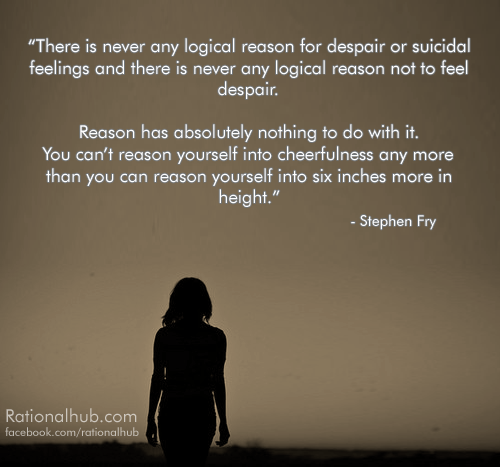

Myth #4: Depression is a choice.

Depression is not something that a person chooses to have! Seriously. A person with depression does not want to feel the way that he or she feels. It is not something that can be willed away any more than cancer or diabetes can. Research has shown depression correlates with chemical changes in the body, which cannot be overcome simply by a change in thinking. Depression is a medical condition that arises from errors in brain chemistry, function, and structure due to biological, psychological, and environmental factors.

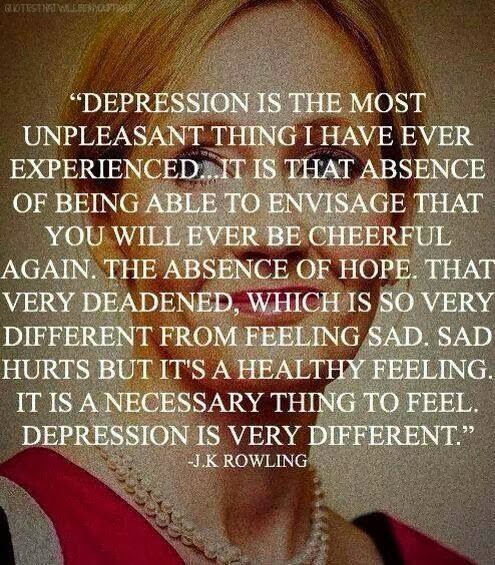

Myth #5: Depression is just sadness/laziness/weakness.

False. Equating depression with any of these things is like saying a common cold is the same as pneumonia.

Depression is not just ordinary sadness, grief, or laziness. Again, to quote Dr. John Grohol:

Depression is overwhelming feelings of sadness and hopelessness, every day, for no reason whatsoever. Most people with depression have little or no motivation, nor energy and have serious problems sleeping. And it’s just not for one day — it’s for weeks or months on end, with no end in sight.Depression is not a sign of weakness--it can strike anyone at anytime. It does not discriminate against gender, race, age, sexuality, religion, culture, or any other factor. Someone with depression is not just feeling sorry for him or herself. Some of the most prominent and accomplished individuals have suffered from some form of depression, including: Alexander the Great, Napoleon Bonaparte, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, George Patton, abolitionist John Brown, Robert E. Lee, Florence Nightingale, Sir Isaac Newton, Stephen Hawking, Charles Darwin, J.P. Morgan, Barbara Bush, Ludwig von Beethoven and Michelangelo.

Myth #6: Depression is just a phase and if ignored, it will go away.

This is false. Depression is a medical condition that requires treatment and support. In fact, many times symptoms of depression will get worse if left untreated. One of the most effective treatments of depression is through behavioral activation. This is the idea that in order to decrease depressive symptoms, one must act opposite to them--activate one's behavior--in order for them to decrease (which will not be instantaneous).

Myth #7: Antidepressants work no better than a placebo and have dangerous side effects.

This one I had to do some extensive research on and the jury is still out on it, not just in my brain, but in the scientific community. Talking about antidepressants, Dr. Azadeh Aalai wrote:

The standard the FDA requires for psychiatric meds to be approved and sold to consumers is not a high one: only two independent studies that yield significant results in favor of drugs is required, regardless of how many trials may be required to render such findings. In other words, “so long as research eventually yields evidence of efficacy, the failures would remain off the books. This is why antidepressants have been approved even though so many studies have shown them to be ineffective” (Greenberg, 2010, p. 216). Moreover, research suggests that the reduction of depressive symptoms seen with antidepressant use may be more indicative of a placebo effect than the merits of the drug itself. For instance, some sources contend that up to 80% of the effectiveness of antidepressants is due to placebo effects (see Greenberg, 2010). This comes at a high cost, given the documented (and not so documented) side effects—chief among them that in some cases, ironically, use of antidepressants actually increases suicidal ideation (particularly among adolescents).A study done by Harvard in 2005 more deeply probed the risks of antidepressants, as did a study at the University of Colorado. Multiple studies have shown the effectiveness of antidepressants over the use of a placebo. People will analyze these studies inside and outside and upside down, but the speculation that antidepressants are no more effective than a placebo has not yet been evidenced in research, and like all medications, psychiatric medications come with their risks and side effects. However, if the medications are taken properly, under supervision of a trained medical doctor, the risks are generally minimal.

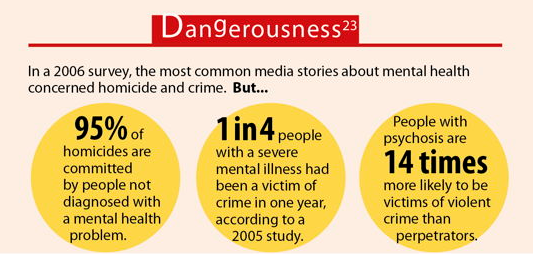

Myth #8: School shootings are caused by antidepressants, proving they do more harm than good.

So. I don't even know what to do with this one. To me, it is a clear case of people assuming that correlation is the same as causation. I did a Google search of school shootings and antidepressants and found not a single credible source in the first few pages of results. To make sure that I was not missing anything, I did a search of PsychInfo, which gave me no results. There has been no research done in the academic community which states a definitive link. I read a statistic (and only one statistic, and not from a valid, peer-reviewed source) that stated 90 percent of school shootings could be linked to antidepressants. Since Newtown, there have been 44 school shootings in the United States, as of February. An estimated 31 million Americans are on antidepressants. That is a very small percentage, even if all those involved in the school shootings were taking antidepressants. Correlation does not imply causation. A link between two things, is not always causal, and in this case, assuming that cause is not only incorrect, but irresponsible AND it continues to promote stigma that keeps people from getting help!

Myth #9: The only way to treat depression is through the use of antidepressants.

Treating depression is not as simple as just taking a pill. Medication alone is not enough and is generally most effective in addition to psychotherapy. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has been shown to be particularly effective in the treatment of depression. Lifestyle changes such as balanced nutrition, regular exercise, and adequate sleep have been shown to help as well as things like mindfulness, meditation, and yoga.

-----

Resources and References:

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression/index.shtml

http://psychcentral.com/lib/an-introduction-to-depression/000650

http://www.nami.org/Template.cfm?Section=depression

http://www.nytimes.com/health/guides/disease/major-depression/overview.html

http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2013/11/13/depression-myths-_n_4268047.html

http://psychcentral.com/lib/what-is-depression-if-not-a-mental-illness/000896?all=1

http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/evil-deeds/200809/is-depression-disease

http://psychcentral.com/blog/archives/2009/10/18/7-myths-of-depression/

http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-first-impression/201302/5-myths-about-depression

http://www.healthcentral.com/depression/just-diagnosed-822-143_3.html

http://psychcentral.com/blog/archives/2009/10/18/7-myths-of-depression/

http://www.healthline.com/health-slideshow/9-myths-depression#1

http://www.hpb.gov.sg/HOPPortal/health-article/10202